“Stand up straight,” Mother said, never missing an opportunity to correct bad posture, even with a client at the door, belly a beer barrel, eyes a pair of cherry pits darting left and right.

Based on the mud layering the stranger’s boots and the fat layering her middle, she’d walked several miles in her swollen condition to get to our house. She told us her name was Marianne, but I had learned never to trust a name. When she reached into her pocket and pulled out the green, I stood aside to let her in.

She pressed one palm into the wall overhead and used the other one to grip her middle.

“Boots off, miss.” There was no way I was cleaning up that mud from all over the house.

“Straighten your apron, Lena,” Mother said, adding, “and get to it.”

Crisis couldn’t keep my mother from making corrections. I ignored her request to take in the stranger.

Wavy black licorice braids cornrowed above a freckled brown face. Swollen breasts, heavy breathing, Marianne, or whoever she was, looked delicious. Unlike most of the women that came to our cottage, she was ripe for the picking.

I imagined myself coming down with her condition. Would I look less gangly when I gained my bulge? Before Marianne, I never understood why any woman would want to conjure up a cure to such beauty.

“Are you deaf, girl?” mother said, snapping fingers in front of my face before tugging my right ear towards the back door. “I said go pick. I swear, girls these days have no social skills.”

Mother sent me to the garden whenever she wanted to talk specifics. Little did she know, I already knew how it happened. What the man did. How he pricked his stick in. I’d seen the dragonflies do it countless times. Male riding female, tandem sky divers.

I preferred to not listen to that part. Out among the plants, I was light as the summer air. The flowers slouched more deeply than I did, weary from the weight of their new blooms. Better to be out of sight, mother always said. The first thing she had me do when we moved in was erect an eight-foot fence.

Whenever a patch of something wiggled its way underneath the fence, I tamed it. That day I noticed the spearmint had grown a stubble, so I bent over and yanked it free, glad when its sweetness spritzed the air. I wondered if the villagers knew what we grew behind our fence. If they did, they didn’t speak of it. After all, a trip to our cottage meant one less mouth to feed come winter.

Mother leaned out the kitchen window to offer more advice.

“Pick from the top, Lena. And today, please.” I had been picking since I was seven and knew how to do it, but I held the sheers high over my head in recognition of her request and went in search of a mature patch of pudding grass. Mother told me it was as easy as clamping the metal instrument on a twig and snapping a leaf free. That’s how the men used to get snipped. Since I’d never seen a pecker, I wondered how much the doctor cut off and how badly it hurt? Did the thing work afterwards? If it was like our leaves, it was good as dead.

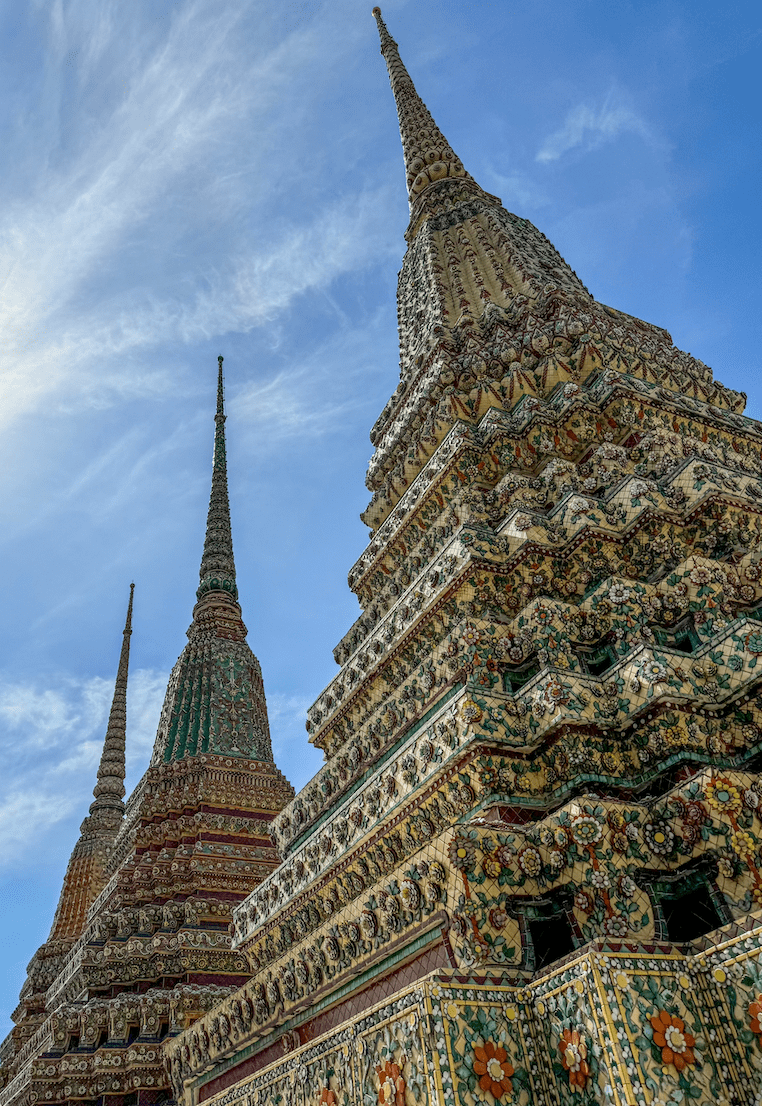

All that remained of hope was a faint trail of painted red signs left on the poplar trees. Every major city had a trail, if you knew where to look for them. Some called it the Underground Abortion Railroad because if you were lucky, the signs would lead you to a grow house like ours. And if you were really lucky, the grower would have a remedy to keep the baby from growing inside of you.

When I was old enough to run my grow house, I would listen to my clients’ stories without interjecting to give my children advice. And if someone ever filled me with a daughter, I told myself I would never nag her about the little things. I would let her make her own mistakes.

Mother would say that’s what went wrong with all the women who visited us in the first place; they grew up wild. “Girls today have too many choices,” Mother said, heating the kettle below boil to make her next batch for a wealthy client who had instead sent the hired help to pick up a remedy.

“But, that makes no sense, Mama. Women today don’t have any choices. That’s why we’re here. To give them a choice.”

“That’s not the choice I’m talking about.” She was talking about the shortage. True, men outnumber women two to one, but we offered the final remedy.

When I found a mature patch, I used my fingers to search through the stems. Mother had taught me which leaves were ready to take and which ones needed more time. The larger ones were useless for making tea, and the smaller ones lethal, if not carefully distilled.

“A more appealing death than a coat hanger,” Mother said, whenever she was worried her batch wouldn’t turn out right.

I snipped a handful and put them in my apron pocket. I never knew how many my mother would need.

When I returned to the kitchen, I was relieved to find the pair had settled into a comfortable conversation.

“We can’t say no, and we can’t service them all.” Marianne barely finished her sentence before her fingernails went into her mouth. She nibbled the edges like a crust of baguette. Since none of her fingers had jewelry, I guessed there was no need no angry husband following her.

“A woman’s worries get heavier, as a man’s worries gets lighter.” Mother consulted her manual and crushed several leaves into the bottom of the glass before pouring water on top.

“Nobody followed me, I don’t think. In fact, I’m sure of it.” Mother laughed because it was never true. The circular motion of her spoon continued uninterrupted. The officers would make inquiry. That much was certain.

“You’re farther along than I’d like. And based on your weight, you’ll need two batches to remedy this…,” she considered her words, “late-term condition.”

Marianne looked down at her belly as if some otherworldly spirit inhabited it. “Flee!” she said, giving her unborn the finger. “Away with you!”

Mother caught her hand mid-fling. Her frown summoned me to her side.

“Lena. Come take a look at this.” She pointed to the woman’s nails.

“I know I shouldn’t bite them. It’s a bad habit.”

I noticed the bite marks from her nibbling right away. Marianne had been chewing for some time, judging by the depth of dead skin. Mother held her middle finger in front of my face.

A tiny, pale, half-moon circle rose from the bottom of her cuticle. Half-moon, pale means… endless blood.

“Anemia?”

“That’s right, girl. Excellent memory.” She examined Marianne’s hand, closed the flesh to form the shape of a miniature globe. With her eyes closed, she spoke to us both. “A special situation calls for a special remedy.” And then turning to me, “Lena, fetch the Royal Tea.”

Royal Tea was the color of an oxidized penny. We kept it on the topmost pantry shelf behind several other exotic blends. The exact ingredients of the tea were one of the few secrets between us.

“We’ll have to make two separate brews,” mother talked to herself while she scooped and measured. “Because of the dose, I don’t advise you travel this evening.”

I folded my arms and scowled at my mother, but she ignored my temper.

“Should I be worried?” Marianne asked, resuming her fingernail snack. “I feel perfectly fine. I promise.”

“It’s no trouble at all. I’ll have Lena make up the guest bed.”

Marianne’s chest grew cherry-colored. She had brought a satchel and a wad of folded bills meant to secure a swift remedy.

“I thought he’d be happy about it, you know. When he got back from his tour, I just knew he’d be thrilled. His wife could never give him one, you see. I didn’t realize my mistake until I felt his fists.” She drew up her sleeve to reveal a lump, swollen purple.

Mother put her hand on Marianne’s shoulder. “Not to worry. You’re expert hands now. Come. Let’s get you to bed so this can all be over.”

I looked to mother for understanding, but she said nothing. I escorted the stranger from the table without meeting her eyes. Mother had taught me to never coddle clients. Never offer lodging. The dangers of housing a woman in her condition were far greater than letting her go off to try their remedy alone. Should anybody discover Marianne under our roof when her red flood returned, they would assume we were to blame.

“No, I can’t stay. I’m expected back by morning. I must leave before sunset.” The girl pushed her crumpled cash towards my mother’s apron.

“Sorry.” mother held up her hand. “No overnight, no treatment.” Marianne’s open mouth made mother soften her tone. “Now come, my dear, you look exhausted. Stay for a rest, and I promise that in the morning, everything will be right as rain.”

“I’m so tired, but I am sure I can’t sleep in a strange bed.” Marianne’s forehead wrinkled and in the sunset’s glow, she looked a decade older.

“Rest your eyes, child. Let the remedy take hold.”

Mother went to sweep the stoop while I put fresh linens on the guest bed. I didn’t think the stoop needed cleaning, but then realized she was keeping a lookout until the sun gave up and granted us some discretion.

Two teas, two trips to the toilet later, I helped Marianne into bed.

I placed her on a special mat meant to absorb a woman’s monthly, but after she climbed in, I wondered if maybe I should have put two mats down. Stained sheets would matter little if we were strung up with clothes lines for helping her.

Marianne’s swollen stomach looked like a white-sheeted ghost. If the baby let go its grip in the night, would it haunt this room forever?

“Care for warm milk?” My mother asked, startling Marianne. Full of the remedy, she turned down the offer with a shake of her head. I was stunned when mother stooped down to give Marianne a quick kiss on the forehead before turning out her bedside lamp.

As soon as we reached the bottom of the stairs, I turned on her.

“What are you thinking? She’s ready to drop that baby one way or another!”

Mother ignored my outburst. “Clean the kitchen mess, then straight to bed.”

I stared at two tiny leaves stuck to the bottom of Marianne’s mug; baby booties never to be worn.

“She’s better off here when it happens.” Mother said, taking the mug from my hands and scrubbing it clean.

I remember the loud knocks that came before the cock’s crow. Mother turned over in bed and put her finger to my lips. I moved below the bed as we’d practiced as she put on her favorite silk kimono, the one with the pink roses, though she never told me where she’d gotten it. She had just put her left arm through the sleeve when armed men broke down the door.

When they shook her, she pointed upstairs to where a world made of flesh awaited. The officers didn’t wait for excuses. They had already prepared a rope on the nearest poplar.

As I watched my mother’s feet go still, I realized her last lesson was one of mercy.

©2024 | K.F. Hartless

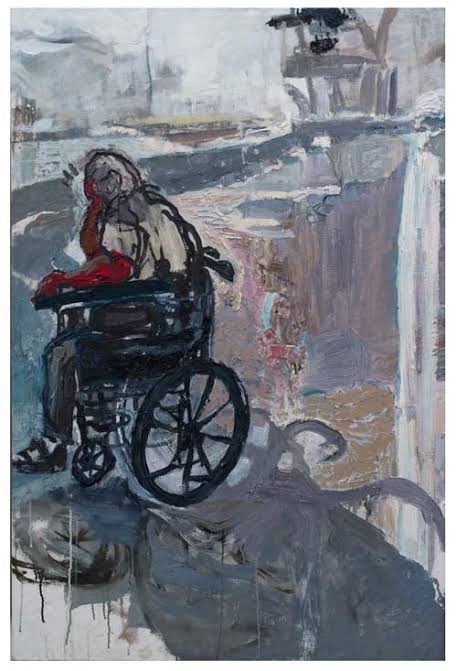

Cover Art: “The Abortion” by Frank Bowling (1934)

Leave a reply to Tom Cancel reply